You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Search for the Sublime’ category.

He had a thing for blue. Also clay pipes and Victorian postcards, ticket stubs, bits of tulle, starfish and old clock parts. He was drawn to automats and secondhand-book stalls, corresponded with ballerinas, filmed pigeons, liked pie.

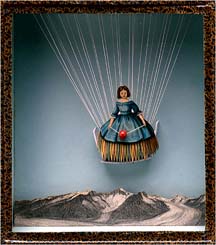

These are among the oft-repeated facts about Joseph Cornell. Notice, in even so brief a litany, the transition from art to life and back again. Perhaps more than any other artist’s work, Cornell’s is best appreciated in the context of imagining the life of the man. Put another way: what Cornell lovers love most may be not the objects themselves — the evocative boxes, collages, dossiers and short films — but the story of their making, which is the story of an awkward dreamer walking the city, finding treasure in flotsam, spying magic all around.

Since his death, Joseph Cornell (1903-72) has been the subject of more than 20 books, from scholarly explorations of his art and life to poetry and fiction inspired by him. Yet for all the scrutiny and the mulling, he remains elusive, almost chimerical: a figure embraced by the art world even as he rejected the label “artist,” a voyager who never strayed far from home, an idolater of innocence whose work could be eerily erotic. In photographs he is gaunt and unsmiling, almost invariably looking away from the lens. His face appears drawn and deeply lined, as if scored by loneliness, and his lean frame has a tentative look, as though he has yet to make up his mind whether he is meant for this epoch, this planet.

Perhaps a desire to understand this enigmatic man in terms that would count him as one of us explains the seemingly endless flow of literary responses to his work. Best known for his glass-covered box creations, many of them made in tribute to people he idealized, Cornell has elicited just as many tributes himself. John Ashbery, Octavio Paz, Stanley Kunitz and Robert Pinsky all wrote poems for him. He’s been immortalized in music and plays. And many of the books about him — from Dore Ashton’s “Joseph Cornell Album” to Charles Simic’s improbably beautiful “Dime-Store Alchemy” to Jonathan Safran Foer’s anthology “A Convergence of Birds” — could themselves be described in Cornellian terms: collage-like, experimental, quixotic. Even those that take the form of conventionally linear narratives (like Deborah Solomon’s definitive biography, “Utopia Parkway”) tend to carry echoes of the magical qualities associated with Cornell.

The latest addition, Lynda Roscoe Hartigan’s mammoth catalog “Joseph Cornell: Navigating the Imagination,” accompanies the first retrospective of the artist’s work in 26 years, a deliciously bountiful exhibition curated by Hartigan and recently on view in Washington, San Francisco and Salem, Mass. If you missed it, this book really is the next best thing: thorough, lavish, disturbing, beguiling…

This book stands out, too, for being utterly unfey, devoid of the poetic eruptions Cornell induces…those who linger may be rewarded, for it turns out Hartigan has done something lovely. She, too, has modeled a response to Cornell’s work on his own methods, assembling and inventorying a pastiche of the ideas, innovations, people, philosophies and experiences that most likely influenced the artist. She doesn’t navigate his imagination so much as map the explicit tributaries that fed it. And is her map ever detailed…

Hartigan’s esoteric, even idiosyncratic approach — heavily sprinkled with illustrations of places, people and objects Cornell encountered — provides a vicarious experience of the man who was himself an idiosyncratic “browser,” drawn to “nonlinear exploration.” The slow accretion of varied and seemingly disparate influences, which Cornell wove together in such singular, suggestive fashion, also lends weight to Hartigan’s intriguing speculation that he might have suffered from synesthesia, the neurological phenomenon that causes some people to “smell” colors or “taste” letters of the alphabet…The crowning stroke to this mapping of Cornell’s mind is the inclusion, in the bibliography, of some 150 books that are not about Cornell but that were important to him, that nurtured and informed his perceptions. Taken together, the words and images offer the sense that we are apprehending the world from the artist’s perspective, rather than witnessing yet another admirer’s artful display. There’s no fault in such a display. Hartigan tells us Cornell thought of art as “a spiritual gift to humanity.” But what she has fashioned is a gift, too, which feels, in its faithfulness, like a special kind of homage.

Cornell gives us hope. The notion of a curious, wistful man walking the city and turning up treasure in debris, seeing the transcendent in the forgotten, the discarded, the mundane — such a notion is intrinsically hopeful. By inviting us to fathom how he did it, Hartigan brings us one step closer to the promise of our own longings.

Leah Hager Cohen

New York Times

Paul Klee Museum in Berne, by Renzo Piano

The notion of a ‘light modernity’ is suggestive. ‘There is one theme that is very important for me,’ Piano remarks: ‘Lightness (and obviously not in reference only to the physical mass of objects).’ He traces this preoccupation from his early experiments with ‘weightless structures’ to his continued investigations of ‘immaterial elements’ like wind and light. Lightness is also the message of his primal scene as a designer, a childhood memory of sheets billowing in the breeze on a Genoese rooftop, a vision that conjures up the shapely beauty of classical drapery as well as contemporary sailing boats as architectural ideals. For Piano lightness is thus a value that bears on the human as well as on the architectural – it concerns graceful comportment in both realms. As a practical imperative, however, lightness confirms the drive, already strong in modern architecture, toward the refinement of materials and techniques, and yet now this refinement seems pledged less to healthy, open spaces and transparent, rational structures, as in modern design, than to aesthetic effects and decorous touches. A light architecture, then, is a sublimated architecture, one that is particularly fitting (that word again) for art museums and the like.

Such lightness is also pronounced in the Museum of Modern Art in New York as renovated by Yoshio Taniguchi in 2004. Its importance to contemporary design was also first signalled at MoMA in a 1995 show called ‘Light Construction’ in which Piano was represented by his Kansai terminal. The curator, Terence Riley, took his cue for the show from another Italian, Italo Calvino, who in his last book, Six Memos for the Next Millennium (1988), proclaimed the special virtues of lightness for the new age: ‘I look to science,’ Calvino wrote, ‘to nourish my visions in which all heaviness disappears.’ The attraction of this dream is clear: it is part of the promise of modernity that free movement will lead to freedom. Viewed suspiciously, however, it is little more than the old fantasy of dematerialisation and disembodiment retooled for a cyber era, and it has become a familiar ideologeme to us all – though it still seems odd that architecture, long deemed the most material and bodily of the arts, would wish to advance it. Viewed even more suspiciously, this lightness is bound up not only with the fantasy of human disembodiment but with the fact of social derealisation: the lightness of the unreal under Communist regimes for Milan Kundera, who proposed this sense of the term before the fall of the Wall, yet under capitalist regimes for the rest of us. This kind of lightness is no ideal at all; it is ‘unbearable’. Perhaps in the end the two notions of lightness must be thought together, dialectically – that is, if dialectics has not suffered its own final lightening, as many people now seem to think.

Hal Foster

London Review of Books

In the early 1990s, while still in high school, Anna Schuleit discovered mystery by taking long walks through the deserted grounds of the Northampton State Hospital. This cluster of Victorian buildings — with its iron-bar windows, crumbling red brick, and chest-high grass — touched a deep chord in the young artist.

“I came to my work as a pedestrian,” said Schuleit…

Early on, she was inspired by abandoned institutional spaces like the old mental hospital. Or by public spaces that allowed for solitude and daydreaming.

Another inspiration was literary: Gaston Bachelard, the French philosopher who wrote about the poetics of space and reverie. “As soon as we become motionless, we are elsewhere,” he wrote of daydreaming, an activity that inspires Schuleit and informs all her work…she said she was taken with Bachelard’s idea of “immensities within ourselves.”

A workshop is important to her as an artist, but “so is always a site, a setting, a real location,” said Schuleit, “a place that can be wandered.”

It is there that a person can have “a dialogue with stillness,” she said. “I believe in the imagination. It is a muscle in the body that can carry us anywhere.”

In 1997, Schuleit’s imagination carried her back to Northampton, where she evaded guards to wander for days of walks on the old hospital grounds…On her walks, Shuleit collected chips of lead paint to display in lines of frame-like glass boxes, talked with former workers at the hospital, and studied old pictures and records. She contemplated the “doubling of misfortune” in the decay of the buildings and the decay of memory — and felt a vivid sadness for the 2,700 patients who over the course of a century had lived there…

In November 2000, after three years of struggles over funding and access, Schuleit turned the old space into “Habeas Corpus,” two days of “celebration” (including testimony from former patients) and performance art. She bought 5,000 feet of sound cable, and with the help of 80 volunteers converted the old mental hospital’s main building into a giant amplifier, “to animate all the voids of the architecture.”

At noon on Nov. 18, for 28 minutes 106 loudspeakers bounced the full sounds of Bach’s “Magnificat” into the interiors, and back out the iron grids, broken windows and ruined arches of the building onto the audience of hundreds standing raptly below…

By 2003, she put together “Bloom,” an installation art piece in Boston commissioned to mark the closing of the Massachusetts Mental Health Center’s main building, built in 1912.

As before, she let the space speak to her, asking officials there only for “a week, an office, a key to every door, and a person who knows every story.” In the end, an impression formed over the years inspired her: “I noticed that nobody received any flowers in psychiatry,” said Schuleit, in contrast to hospital stays for heart attacks or broken bones.

So using hospital records, she calculated how many patients had been committed there since 1912, “bringing together all the flowers they had never been given.” The answer: 28,000 potted — not cut — flowers (so they could be given away afterwards). Shipments included 15,000 tulips from Canada, stacked high in an 18-wheeler.

Schuleit transformed hallways into rivers of flowers. The chairs in a waiting room looked like islands in a sea of flowers. An abandoned swimming pool, used to store furniture, was filled with 3,000 blue African violets. Floors in the basement, where the laboratories had been, were carpeted with live turf “that came in rolls, like sushi,” said Schuleit.

“It was a crash course in colors,” she said of “Bloom,” — and for viewers, a font of tears for the departed and the forgotten.

Serious leaders who are serious readers build personal libraries dedicated to how to think, not how to compete…Perhaps that is why — more than their sex lives or bank accounts — chief executives keep their libraries private. Few Nike colleagues, for example, ever saw the personal library of the founder, Phil Knight, a room behind his formal office. To enter, one had to remove one’s shoes and bow: the ceilings were low, the space intimate, the degree of reverence demanded for these volumes on Asian history, art and poetry greater than any the self-effacing Mr. Knight, who is no longer chief executive, demanded for himself.

The Knight collection remains in the Nike headquarters. “Of course the library still exists,” Mr. Knight said in an interview. “I’m always learning.”

Until recently when Steven P. Jobs of Apple sold his collection, he reportedly had an “inexhaustible interest” in the books of William Blake — the mad visionary 18th-century mystic poet and artist. Perhaps future historians will track down Mr. Jobs’s Blake library to trace the inspiration for Pixar and the grail-like appeal of the iPhone.

If there is a C.E.O. canon, its rule is this: “Don’t follow your mentors, follow your mentors’ mentors,” suggests David Leach, chief executive of the American Medical Association’s accreditation division…

Forget finding the business best-seller list in these libraries. “I try to vary my reading diet and ensure that I read more fiction than nonfiction,” Mr. [Michael] Moritz said. “I rarely read business books, except for Andy Grove’s ‘Swimming Across,’ which has nothing to do with business but describes the emotional foundation of a remarkable man. I re-read from time to time T. E. Lawrence’s ‘Seven Pillars of Wisdom,’ an exquisite lyric of derring-do, the navigation of strange places and the imaginative ruses of a peculiar character. It has to be the best book ever written about leading people from atop a camel…”

Poetry speaks to many C.E.O.’s. “I used to tell my senior staff to get me poets as managers,” says Sidney Harman, founder of Harman Industries… “Poets are our original systems thinkers,” he said. “They look at our most complex environments and they reduce the complexity to something they begin to understand.”

He never could find a poet who was willing to be a manager. So Mr. Harman became his own de facto poet, quoting from his volumes of Shakespeare, Tennyson, and the poetry he found in Arthur Miller’s “Death of a Salesman” and Camus’s “Stranger” to help him define the dignity of working life — a poetry he made real in his worker-friendly factories.

Mr. Harman reads books the way writers write books, methodically over time. For two years Mr. Harman would take down from the shelf “The City of God” by E. L. Doctorow read the novel slowly, return it to the shelves, and then take it down again for his next trip. “Almost everything I have read has been useful to me — science, poetry, politics, novels. I have a lifelong interest in epistemology and learning. My books have helped me develop a way of thinking critically in business and in golf — a fabulous metaphor for the most interesting stuff in life. My library is full of things I might go back to.”

Harriet Rubin

New York Times

Richard Long is one of Britain’s most influential living artists. Based on the artist’s walks from the mid-1960s, his work takes the form of photographs, maps, drawings and sculptures (generally lines or circles constructed from natural materials). A new exhibition at the Scottish Gallery of Modern Art (June 30 – October 21 2007) will span the artist’s career and feature a number of new works created specially for the show…

For more than 40 years, Long has insisted on his art’s simplicity. This goes against the grain of modern life, which is one of the reasons why Long’s work is worth returning to. The limitations are part of the pleasure. Simplicity is reason in itself. A new book, of the artist’s collected statements and interviews, returns again and again to this same basic premise, the same plea to keep things uncomplicated, in our approach as much as his.

Famously, Long walks, though he has been known to cycle and to travel by kayak. He goes in straight lines and in circles. Pacing back and forth, like a writer in a room in search of an idea, Long once walked the grass flat in an English field. He has also circumnavigated mountain ranges, used dried riverbeds as paths, and followed his compass and a line ruled on a map to find his way across Dartmoor and the high plains of the Canadian prairie.

Once, on a 15-day walk in Lapland, Long turned 207 stones to point into the wind. Sometimes, a text on a gallery wall is the only record that the artist went somewhere with some small, entirely useless yet significant aim in mind. More often, he photographs what he has done and the places he has been. These photographs – always using the same camera, the same lens – are often accompanied by a few lines of text. They are more than just a record.

Ireland, Scotland, the Australian outback, Kilimanjaro, the Himalayas, Berkshire: the exoticism of the location isn’t what matters, but it helps. Looking at Long’s photographs in a book, we imagine journeys we shall never take, places where we shall never stand. There is a sadness in this. The words Long uses are like the stones and sticks he picks up along the way. They are descriptive, declarative and plain, and just a few of them put next to one another are enough to take the reader somewhere else. The line “Earthquake in the forest” is dizzying enough. Long insists his words are not poems. I guess for him they might be sculpture, which is what the US conceptualist Lawrence Weiner also says about his own use of words on the wall. Or perhaps words for Long are a kind of drawing.

But the walk’s the thing. Long has fallen in rivers, narrowly avoided being shot by a farmer in Montana, and been beset by natural and unnatural hazards of all kinds, but the drama is mostly kept off stage, out of sight, a traveller’s tale we are not privileged to hear.

Sigmar Polke installation at the Biennale

Most of us who attended the Biennale’s three press days last week agreed that this is the best Biennale we had seen in years.

There are several reasons for this. First, many of the leading nations have made their best curatorial picks in a long time…Second, the artistic director of this year’s Biennale was Robert Storr, the former senior curator of painting and sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Now dean of the Yale University School of Art, he is indisputably one of the great curators working today, making exhibitions that display both a high degree of aesthetic discrimination, a depth of historical understanding and an impeccable sense of timing.

The German artist Sigmar Polke has been granted the most prestigious spot in the exhibition – the large, sunlit central gallery of the pavilion, in which he is showing enormous semi-transparent bronze-coloured canvases that look like glazed or oiled skins. These are encrusted here and there with imagery drawn from historical illustrations or the history of art. (The figures looked to my eye like explorers or philosophers, some like angels.) Standing back to enjoy these works, you can sometimes see through to the wooden struts that support the canvas from behind. Artifice and the means by which it is made are interpolated, and you find your mind shuttling between the courtly art of the grand European tradition and the primitive imperatives of nomadic cultures. Polke’s vision is encyclopedic.

Around the corner, Storr has installed a killer lineup: Ellsworth Kelly from the U.S. (showing crisp, split-level abstractions), Germany’s Gerhard Richter (a suite of massive multicolored pictures made by scraping pigment sideways on the canvas surface, often suggesting corrupted digital or photographic imagery) and Robert Ryman, the American master of the white-on-white canvas, who is showing new works subtly edged in blue. Taken as a whole, this lineup of senior statesmen seems to demonstrate the vast psychological and aesthetic terrain that painting can cover with the simplest of means – just paint and canvas. Engaging our senses with colour, texture and composition, Storr’s battalion of master painters lays siege to the mind.

Storr never seems to tire of defending painting, but sometimes this enthusiasm leads to uncharacteristic lapses in discrimination. The only weak moments in his show, in fact, occur in the painting department, where he included his long-time American favourites Elizabeth Murray (garish extravaganzas that are to me inexplicable) and Susan Rothenberg (rough-hewn horse paintings that likewise seem a bit dim), and a number of lesser known painters who fail to pass muster (such as Izumi Kato from Japan and Thomas Nozkowski from the United States).

The balance of the show, however – the sculpture, photography and projection works – more than make up for this. A theme emerges: Storr versus CNN. Taken as a whole, this exhibition presents a kind of sustained resistance to the smarmy platitudes and easy generalizations of the media, which so effectively gloss over the jagged edges of confusion, human tragedy and loss. Truth is to be found, Storr seems to suggest, not in grand and sweeping rhetoric. Rather, it is lodged in the nitty-gritty of lived experience, which art can make us witness to…

One of the ironies of the Biennale is that you walk from inside these galleries, where political and emotional trauma are so often the subject of art, into the blaze of the Venetian afternoon, with its pigeons, its fruit stands, its gondolieri singing Volare and its delirious tourists spooning up their hot-pink gelato di fragola in great melting spoonfuls. The contrast can be corrosive.

Storr has managed to select artists whose handling of dark themes is untainted by sensationalism and glibness, and that’s no mean feat in today’s art world. The works hold up, even against all this supreme silliness. Considering the show in retrospect, you feel chastened and inspired to expect more from art, and to think a little more rigorously about how we live. This show’s intelligence leaves a taste in your mouth that not even ice-cold Prosecco can wash away.

Sarah Milroy

Globe and Mail

American art historian Kirk Varnedoe, in Pictures of Nothing, the series of Mellon lectures on abstract art since Jackson Pollock that he delivered shortly before his death in 2003, made the sometimes overlooked point that not all abstraction has been about “its noisy, declarative protagonists”; that, in fact, almost “a quarter of contemporary abstraction … is about whispers, innuendo, confidences exchanged intimately rather than publicly declared”.

“We don’t want our personality in the art,” Ellsworth Kelly once said. “We all had to get over Picasso, because his was ‘great personality’ art. We were trying to get away from the ‘I’, as in ‘Look how well I do it.'”

There is a noticeable strand of solitariness in recent American art, of city-born artists leaving the cities in pursuit of what might be thought of as anti-experience – attempts to quiet the mind.

Kelly’s great friend and contemporary Agnes Martin…fled the Manhattan of the 1950s for the flat, open spaces of New Mexico. There, for the next 40 years, she devoted herself to making paintings which, as she put it, “have neither object nor space nor time nor anything – no forms”.

The numinous quality of Martin’s paintings – the way light seems to be stored up inside them – has inevitably evoked a spiritual experience. Such responses have been encouraged by Martin’s writings, which extol the virtues of the solitary life. “I suggest to artists that you take every opportunity of being alone, that you give up having pets and unnecessary companions,” she once wrote. “I suggest that people who like to be alone, who walk alone, will be serious workers in the art field.”

Horn’s Library of Water in Stykkisholmur, Iceland

Horn has been a “permanent tourist” in Iceland from her home in New York for more than 30 years. Library of Water, her permanent installation in the small coastal town of Stykkisholmur, three hours from Reykjavik, has just opened to the public for the first time. Water has been “archived” from glacial sources in all parts of Iceland and decanted into a copse-like stand of transparent glass columns that have replaced the shelves where books were once stacked. Some of the columns are clear, others are opaque, with traces of ancient debris drifting in them. The debris is a reminder that the glaciers were formed many millennia ago and are rapidly receding. Horn describes Library of Water as “in some sense an end-game, since many of these sources will no longer exist in a matter of years”. But Vatnasafn, to give it its Icelandic name, isn’t primarily an ecological/political work; it isn’t agitprop.

Horn imagined Library of Water as a place for quiet observation and reflection, “a lighthouse in which the viewer becomes the light. A lighthouse in which the view becomes the light.” This connects it to her work of the past 30 years, which has ranged across drawing and sculpture to photography and essays, and whose guiding principle has been anonymity on the part of the artist and minimum intervention in the work’s execution. She has spoken many times of her “desire to be present and be a part of a place without changing it”. Detachment, humility and surrender, that is the ambition. She’s there, and then she isn’t there, like the weather…

Horn was born in 1955. There are now monuments to the achievement of artists just a generation older all over the United States. Following the model of the Rothko Chapel in Houston, the minimalist shrines range from James Turrell’s Quaker meeting house in Houston, to Donald Judd’s museumification of the entire town of Marfa, Texas, to Walter de Maria’s mile-wide Lightning Field in Quemada, New Mexico.

These are projects on a grand scale. Roni Horn’s Library of Water in Stykkisholmur (population 1,100) on the north-west coast of Iceland, on the other hand, is modest, unassertive and intended to serve the community rather than coerce it into an appreciation (or even a viewing) of the work of one of the more recondite practitioners of conceptual art. In addition to the two installations of Horn’s work – a rubber floor scattered with childishly rendered words in Icelandic and English, and the glacial water housed in its top-lit, floor-to-ceiling columns – the space will be used by the local community for activities ranging from yoga classes and AA meetings to gatherings of the local (women-only) chess association and reading groups.

Lama Anagarika Govinda says that “if we look at a landscape and imagine that what we see exists as an independent reality outside ourselves, we are the victims of an illusion. If, however, we see the same landscape represented in the work of a great artist, then—in spite of the fact that the painting creates the visual illusion of a landscape—we experience an aspect of reality, because we are conscious of the illusion and accept it as an expression of a real experience….The moment we recognize an illusion as illusion, it ceases to be illusion and becomes an expression or aspect of reality and experience.”

But what happens if the work of art is not an illusion, but is a life that is being lived? Is it still art? Or has it then become a matter of “right livelihood?” As Nancy Wilson Ross describes it, “if a job help us in our search for an understanding both of ourselves and of the world around us, then it is, for us, samma ajiva (right livelihood)—no matter how futile and crazy it may seem to our friends and neighbors.” This may very well describe what art does for its maker—at least in part, and for some makers.

Marcia Tucker

White Paper II

Image courtesy of Michael Werner Gallery

As is always the case with his work, Mr. Polke said, the paintings for the biennale sprang from specific ideas yet evolved in mystical ways as he experimented. “This is the meeting point of ideas and materials coming together,” he said in his German-accented English. “You see what you want, but you have to work with the painting, and the results are always different.”

Altogether, it has taken him two years to apply and dry the poured lacquer surfaces of the seven abstract paintings he has created for the Biennale. Jointly titled “The Axis of Time,” they are to form the heart of the biennale’s signature exhibition in the Italian pavilion, called “Think With the Senses — Feel With the Mind. Art in the Present Tense.”

The show was organized by Robert Storr, the artistic director of the biennale and a former curator at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Given that he views the exhibition as “a meeting place of conceptual and perceptual art,” Mr. Storr said, it was a natural choice.

“Polke for a long time has been the most interesting, least predictable of the painters around,” he said by phone from Venice. “He’s almost impossible to get a bite of. People don’t know what to say right off the bat when they see his work. It has a deep kind of shrewdness.”

Nicholas Serota, director of the Tate in London, who has exhibited Mr. Polke’s work since 1995, said that quality of inscrutability played into the fascination. “He turns base metal into gold and base fabrics into great paintings,” he said. “But he is a very difficult artist to get hold of. He makes Richter, who’s complicated, look simple.” (Mr. Polke is often grouped with Gerhard Richter because both came of age and experimented in West Germany in the 1960s.)

Carol Vogel

New York Times